Photo by Margie Beaton

Reflections from the Gaelic Narrative Project team

In July, the GNP team went offline and off the beaten track in search of a more nuanced understanding of narratives related to Gaelic culture and history. We didn’t have a grand plan—we just followed our curiosity and took advantage of opportunities as they arose.

Later, as we turned the corner into September, the team came back together to compare notes and reflect on the summer’s adventures. We soon realized the learning had been personally impactful and many-layered, and we wondered how to share our experiences beyond the team. We were especially aware that many people in the GNP network are outside Nova Scotia and unable to join in-person events. Susan Szpakowski offered to weave some of the threads from our debrief conversations into a blog post that could be shared with others.

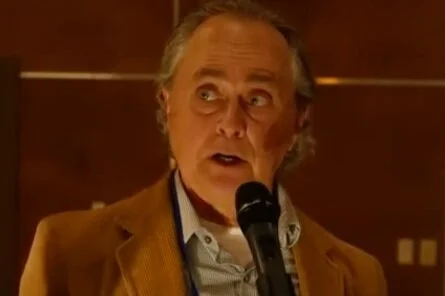

Unpacking narratives: Visits with Michael Newton

Our summer adventures began when we learned that visiting Gaelic author, historian and teacher Michael Newton was on a province-wide speaking tour. We invited him to lead conversations in Mabou and then in Halifax, where we could explore shadow narratives within the Gaelic community. What stereotypes—both historical and current-day—have negatively impacted the way Gaels themselves perceive the significance and value of their own language and heritage?

In both conversations, the sharing was personal and sometimes poignant. We heard that in recent generations many children grew up with the stigma that Gaelic was rural, backwards, associated with poverty, and had no future. Young Gaels were told that learning the language would get in the way of their future success.

GNP team member Bernadette Campbell described the Michael Newton conversation in Mabou as a “safe space” where she felt heard, and was able to admit that it’s been challenging to hold onto an interest in learning the language. She was one of 12 children raised by Gaelic-speaking parents and grandparents, yet only English was spoken at home. She remembers hearing comments like, “What’s the point—you can’t eat Gaelic, it has no economy.” Bernadette reflects, “Phrases like these can resonate for a long time, and I think they really impact whether you feel you have the capacity, the commitment, or even the reason to pursue learning Gaelic or connecting with it in some way.”

She adds that she’s realizing language learning isn’t all-or-nothing. “Even just learning about how a parent or grandparent might have used a particular word is a window into the culture. Maybe there’s humour in it, there's remembering in it, and connecting with history, and if you're having that conversation with someone, it becomes a shared cultural experience.”

The Halifax meeting with Michael Newton surfaced many of the same themes, though it began with a moment of tension when someone said they “hadn’t heard any of that”—they had only experienced appreciation for Gaelic culture. Michael was visibly taken aback and later admitted he’d been triggered by the comment. In our end-of-summer conversations, GNP team member Mike Kennedy recalls that he and Michael Newton used to take about negative narratives 30 years ago, when they were both post-grad students in Edinburgh, so he could understand Michael’s moment of impatience. He says, “Sometimes we forget that other people haven't been thinking about these things. People of Irish or Welsh ancestry would understand, as they were in a similar position to the Gaels. We all got sucked into the largest empire on earth and it was a brutal event, with 700 years of oppression, warfare and famine. At the same time, since then we've all crossed over, become lumped together as ‘white.’ Some of us enjoy being successful, part of the dominant group. Others definitely see us that way. They see Gaels as being part of the British Empire that steamrollered over everybody else. So I think these meetings were a great opportunity to bring out some of those hidden stories without judgment. People could share their experience, like the person who said they were asked, ‘Why would you want to learn a dead language?’ We can take stories like that apart and understand where they're coming from.”

In each meeting, the brainstorm of negative narratives was followed by a round of naming the positive counter-narratives—the stories we want more of. This exercise took us into the values that have lived on at the centre of Gaelic culture and language, even though they often run contrary to the agenda of assimilation. The groups asserted that for Gaels “well-being is not just defined in material terms,” but is tied to the life of community, culture and spirit. Because of this, “reclaiming culture enhances a sense of connection, self-worth, and purpose.” We also saw that our own “confidence and self-worth are vital for good relations with others and the road to ally-ship and decolonization.”

Connecting with ancestors: Céilidh na Beinne

On July 14, about 20 Gaels hiked up the Cape Mabou trail to the ruins of the pioneer MacPhee Settlement, where they shared stories, songs and music. Each person placed a stone at the site of the old homestead, building a small cairn of gratitude for the toils and gifts of their ancestors.

Mike remembers that the idea to do something simple on the land was sparked last spring when he tried to schedule a call with a friend in Ireland. She told him, “I can't talk this weekend because a bunch of us are going to the Blue Mountains in Donegal for Beltane. We’ll walk up there and play some tunes, sing some songs, and tell stories, mostly in Irish and Gaelic.” Mike was struck by how natural and organic this all sounded. He knew that Beltane was an important day in the Celtic calendar and the Blue Mountains were sacred, literally the place of legends. He realized that there wasn’t the same close connection between land and culture in Cape Breton, but we could at least do more to remember the connections that were there—and grow new ones. Mike dreamed of groups going to places where the Gaels first settled and imagining what it was like for them, how difficult it was. They worked hard, and their stories would remind us that we can also overcome obstacles to keeping our culture alive. Like the group heading to the Blue Mountains, it needn’t be complicated. And if it started somewhere, maybe the idea would spread.

Not long after, Mike ran into Dougie MacPhee, who is on the board of the The Mabou Gaelic and Historical Society. He had an idea to invite some folks to visit the ancestral MacPhee homestead on the Cape Mabou trail, and began organizing Céilidh na Beinne. He connected with GNP team member Frances MacEachen, who works with Gaelic Affairs in Mabou, and together they planned the event that drew on principles of the on-line Gaelic Narrative Project. "I thought, why don’t we just have a visit up there," she said. "In the agenda we left time for people to reflect and make meaning together. We created a small cairn, each person saying the name of an ancestor as they placed their stone. A couple of us sang Gaelic songs and we ended with a Gaelic blessing. It was simple and beautiful. I think it worked really well.”

Bernadette agrees. “It was just so lovely to have a purposeful moment. When I placed my stone I remembered a woman I met in Scotland who encouraged us to hold our space here in North America as Gaels. I find in our Western world we're not often called to take moments— whether to remember or just take a breath and imagine possibilities for the day or the future. I really appreciated that.”

Just as Mike had imagined, word got out and a group in another part of the province said they wanted to do something similar. GNP member Margie Beaton suggested the team put together a toolkit with a few principles and examples. That way any community could easily plan their own outdoor “visit” for remembering ancestors and forging connections between culture and land— and maybe even for celebrating traditional Gaelic holidays in these places, as Mike’s Irish friends had done a few months earlier.

When thinking about suggestions for the toolkit, Frances remembered standing at the MacPhee Settlement, wondering about the people who had been there before—the Indigenous Mi’kmaq. Would they have traveled through here on their way to coastal fishing grounds? What was their name for this beautiful place? Frances thought that perhaps at future events, an opening land acknowledgement could be more than the usual one sentence. Maybe it could include Mi'kmaw placenames and stories learned by being in respectful relationship with neighbouring Mi’kmaw communities.

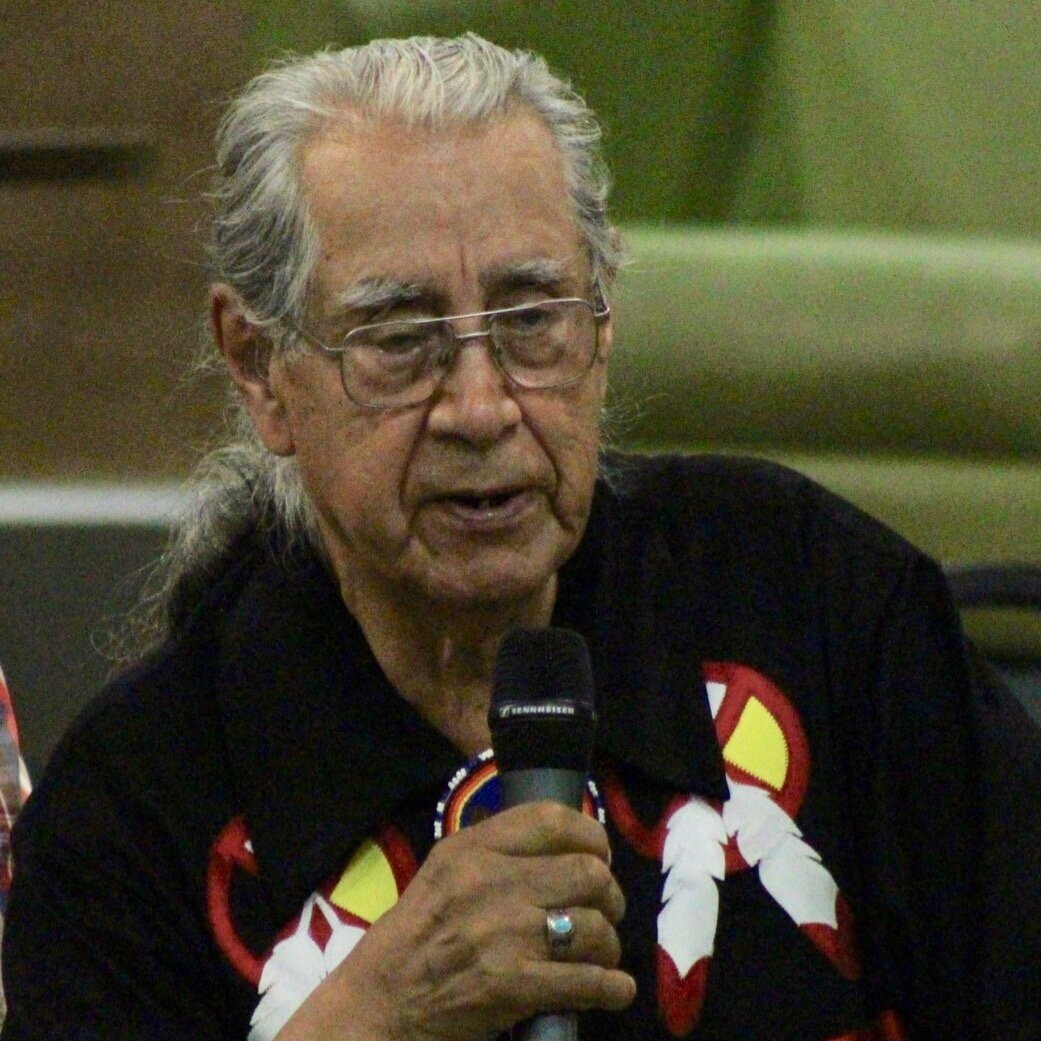

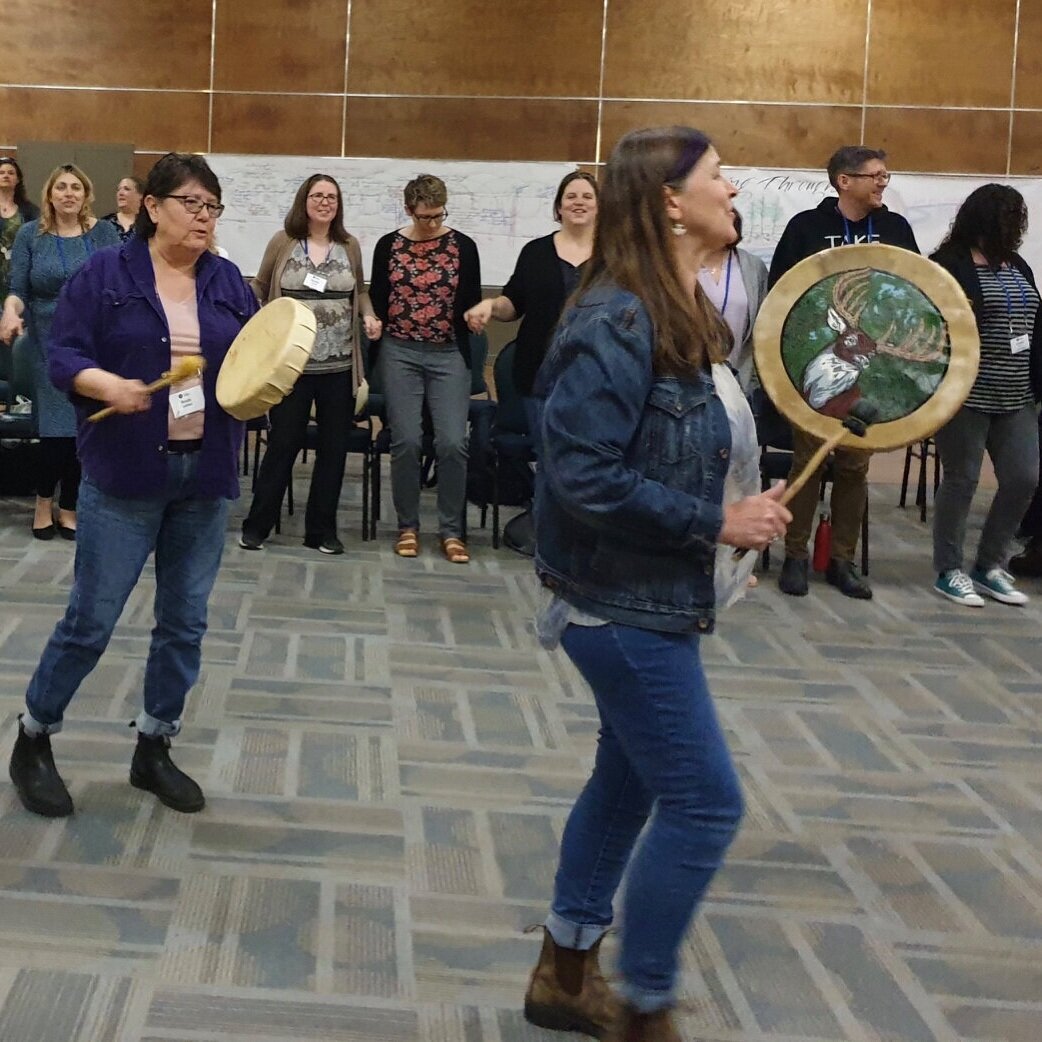

Building Bridges: Cultural tour at the Skye River Trail

On a beautiful day in late August, the team from the Skye River Trail in the Mi’kmaw community of We'koqma'q, Unama'ki (Cape Breton) generously hosted Gaels and others for an afternoon of cultural exchange. We learned about the traditional game of Waltes and the beauty and variety of Mi’kmaw baskets. We tasted restorative berry teas, identified medicinal plants growing near the river, and enjoyed a delicious feast. We came together in a large circle and learned Mi’kmaw dances and songs, shared some Gaelic tunes, and exchanged gifts. At the closing, Elder Susan Copage spoke to the circle, saying that now it was up to all of us to share stories of learning and friendship from this day, and to carry that spirit forward.

The GNP team agreed that this day had been special, a true gift. The event had grown out of a series of meetings initiated by Bernadette and joined by Frances. Bernadette recalls, “At each meeting we discussed many details about the gathering and how we could make it lovely for the visitors, but we were also learning about each other—assumptions we each had, our cultural beliefs, ideas and stories. I had been on the trail several years earlier and felt it was a healing place. The Skye River team certainly knew that, and they were so open to sharing that with us. As we talked, we would inevitably end up sharing a desire to make meaning with each other in terms of those things we each hold dear about our cultures, languages, and so on. That desire always seemed to show up.”

Frances remembers that when she and Bernadette arrived at the first meeting, a member of the Skye River team greeted them and said, “You folks experienced a genocide too.” It was a surprising comment that carried an acknowledgement of Scottish history—that the Gaels had also been oppressed and displaced. Frances adds, “But then when I think about all the land that was granted to those early Scottish settlers, it is obvious that we then displaced the Mi’kmaq and history repeated itself. I just wonder, how do we stop repeating this colonizing? And given all that, I'm just blown away by the enthusiasm and generosity of the Mi’kmaq to host settler groups.”

The GNP team had already been thinking about digging deeper into historical narratives and making connections with intergenerational trauma and colonial legacies. Frances said she felt that this summer’s in-person meetings helped to make some of those threads more visible. She said, “Maybe it’s time to literally start choosing the stories we want more of.”

Bernadette took away from the meetings a deepened appreciation for the hard work the Mi’kmaw women were doing in their communities. “At our last meeting I had a glimpse of all the ways the women in the Skye River team are carrying their culture forward in their families and communities. They are remembering their culture and integrating practices into their lives. Susan Googoo, the director of the team, said something that really resonated with me, which ties into my experience as an adult language learner. So often I hear Gaels saying, ‘Our parents never spoke to us in Gaelic, except when they didn't want us to understand.’ Susan told us that Mi’kmaw words show up in her daughter's dreams, and she tells her daughter those words were meant to be there. When I heard that, a light switched on for me. In the last two years I’ve had so many moments when Gaelic words show up—not in my dreams, but in my speech. I have a moment of realizing, wait a minute, that’s not English, that’s Gaelic. I believe Susan was telling us that our ancestors are always here, and when their words and the knowledge are prompted to come into this world, they are meant to be shared.”

When the GNP team debriefed the Mawi’tane’j Céilidh, Margie said, “That day will stay with me for a long time. My only fear is that it will be a one-off, a token event. I had so many moments of seeing someone from the Mi’kmaw community and thinking ‘you look familiar.’ Because I grew up in Mabou, we were all neighbours and some of us went to school together. At the same time, we were worlds apart, and I’m just realizing how much work there is to be done. We’ll never know all of what comes out of that day, but I sincerely hope it was just a beginning. I have a craving for more.”

This summer we learned that narratives are a doorway into deeper levels of understanding and healing. Online and on the land we have been re-authoring the céilidh as being less about performance and more about sharing stories and conversation, making meaning, and living our culture with warmth, hospitality and good humour. By bringing a spirit of curiosity and bravery to the shadow narratives that hold us back, we can begin to choose the stories we live by, both within our own culture and in our relationships with our Mi’kmaw neighbours.

Tracy George. CEPI Youth connect young people in Cape Breton/Unama’ki with each other and with business opportunities.